Bluebird Bio: On The Cusp Of A Gene Therapy Revolution

Nick Leschly talks to PME about Bluebird's remarkable gene therapy pipeline and why it’s filing first in Europe.

The US biotech company aims to have four groundbreaking gene therapies launched by 2022 – with the promise of lives transformed in each of these rare blood diseases – and realistic hope of a cure for many patients. CEO Nick Leschly (pictured below) talks to PME’s Andrew McConaghie about the company’s ambitious plans, and why it’s filing first in Europe.

Cell and gene therapy made the transition from an interesting but unproven science to medical reality in 2017, with two ‘living medicine’ CAR-T drugs, Novartis’ Kymriah and Gilead/Kite’s Yescarta and Spark Therapeutics’ gene therapy Luxturna all reaching the market last year.

These products are true breakthroughs in biotech science, because they promise to provide a lifelong cure for at least some of the patients they are administered to – and all in just one infusion of genetically modified cells.

Cell and gene therapies are not just revolutionising clinical outcomes, but also in how healthcare systems administer treatment to patients, and how those healthcare systems will pay for them.

The next company to play its hand in this biotech-led transformation of medicine will be Bluebird Bio. The Cambridge, Mass-based company is set to file the first of its four candidates, LentiGlobin TDT, a gene therapy for patients with the rare blood disorder beta thalassemia, by the end of 2018.

If you look at the results, you can’t help but say, wow, there is a lot of hope in that data," says Leschly.

"We think it could be very important for patients and their families, and if that is the case, then the system has a tendency to pay attention."

Pharmaceutical Market Europe spoke to Bluebird’s CEO Nick

Leschly shortly after it unveiled data at the EHA congress last month, which provided further confirmation that its LentiGlobin platform transformed the lives of transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia patients. Eight out of ten ‘non-ß0/ß0’ patients (those with moderately severe disease) in a trial had been freed from the need for blood transfusions for the first time in their lives, with the effect lasting a median of 33 months after just one treatment.

While previous read-outs had prepared the ground for this remarkable result, a similar success in sickle cell disease also unveiled at EHA came as a very welcome surprise for the company, investigators and patients. Interim trial data showed the therapy can reduce by 30-60% the sickling of red blood cells, which causes acute pain and organ damage in sufferers.

This was well above the threshold Bluebird has set for a clinically relevant response, and could also represent a de facto cure for patients.

Now making final preparations for filing in beta thalassemia with the Bluebird team, Leschly expressed confidence that the gene therapy could transform the lives of many patients – and would therefore also overcome pricing and reimbursement obstacles.

“If you look at the results, you can’t help but say, wow, there is a lot of hope in that data,” says Leschly. “We think it could be very important for patients and their families, and if that is the case, then the system has a tendency to pay attention.”

Unusually, Bluebird has decided to file with Europe’s regulator the EMA first, rather than the US FDA, which means European patients are set to benefit from this groundbreaking medicine first, with an EU launch and approval expected in 2019.

Excitement has been building around the company’s lentiviral vector-based platform for a number of years, but the last 12 months has seen it overcome earlier doubts with a string of compelling data readouts which confirm that Bluebird has several major products on its hands.

However the company isn’t home and dry just yet – while approval for its first product looks highly likely, it’s not a guarantee that the treatment will be a commercial success. Europe has already seen two gene therapies approved but fail commercially – UniQure’s Glybera and GSK’s Strimvelis – and so Bluebird has to learn lessons on pricing and reimbursement and build the infrastructure required to administer the therapy safely and efficiently to patients across the continent.

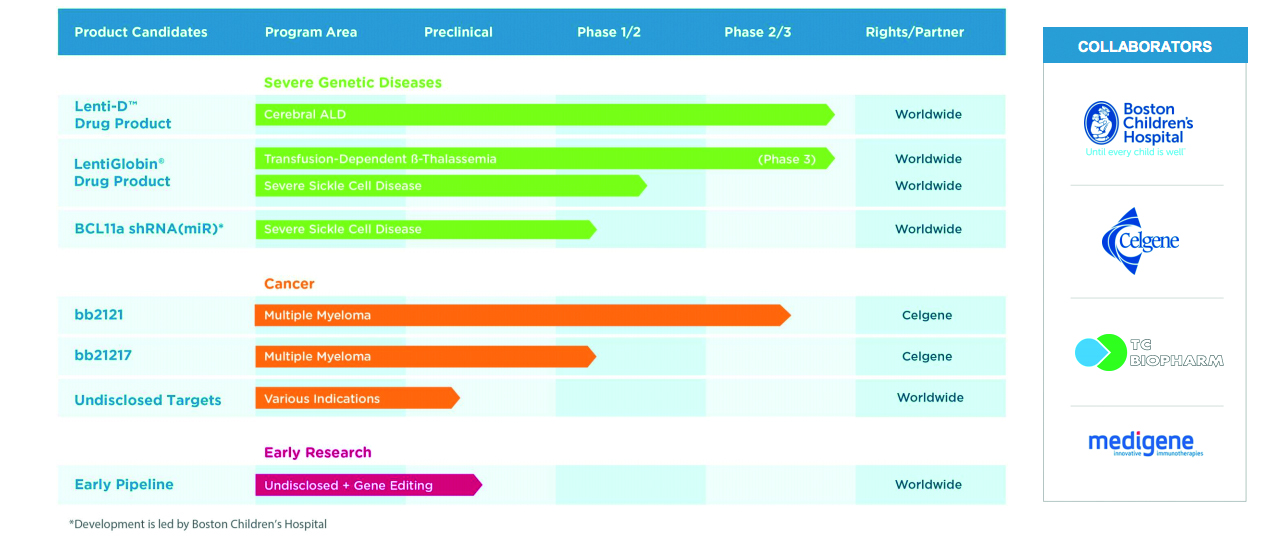

Bluebird’s four breakthrough candidates

In addition to the two LentiGlobin-based treatments, the company also has its Lenti-D product for patients with cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy (CALD), a rare, serious and life-threatening hereditary neurological disorder.

A New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) publication highlighted Lenti-D’s efficacy in cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy, with 88% patients alive and free of major function disability. The company is due to report its Starbeam data by the end of 2018.

Its fourth pipeline candidate is the multiple myeloma targeting CAR-T therapy bb2121, being co-developed with Celgene, which is tipped to be Bluebird’s potential blockbuster and therefore most crucial to its future.

On 1 June it presented data on bb2121 at ASCO which showed the therapy could stop the disease in its tracks in the sickest patients, where all other treatments had failed.

Analysts think bb2121 could gain approval by 2020 and hit peak sales of $5bn, leading a crowded CAR-T field in the disease.

“I think this is the first time ever where a biotech has its first four programmes all heading towards filing and commercialisation in such a short period of time – that’s a remarkable hit rate,” says Leschly. “Also, if you look at each of those programmes, it is not just a first generation, but a second generation coming close behind, so we’re constantly reinventing the areas we are working in.”

There is no question that these products are truly groundbreaking: three have FDA Breakthrough Therapy Designation and two have the similar PRIME designation from the EMA.

The sickle cell programme has also been named on the FDA’s Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy designation (RMAT), a new fast-track specifically aimed at helping these cutting edge medicines gain approval.

The company has come a long way since 2010, when Leschly and a group of investors took over the ailing Genetix Pharmaceuticals (first set up in 1993) from its founder Philippe Laboulch, reinfused it with cash and renamed it Bluebird Bio.

Progress has often been slow, with many setbacks and concerns about safety, efficacy and commercial viability of gene therapies.

Jesse Gelsinger

Probably the biggest blow came in 1999 when a young man named Jesse Gelsinger died when he took part in a gene therapy trial run by the University of Pennsylvania, and fears about safety deterred much investment for many years.

However a small group of academic scientists maintained their focus in the field, such as Kathy High, emeritus professor of paediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, and today president and chief scientific officer of Spark Therapeutics.

There were numerous lessons learned from the death of Jesse, with one of the biggest being the decision by those continuing research to abandon the adenovirus used on Gelsinger in favour of a more stable adeno-associated virus (AAV) – which now forms the basis of Spark Therapeutics’ drugs and, in Bluebird’s case, the lentivirus.

Nick Leschly says even years after Jesse Gelsinger’s death, there was limited confidence in the field.

“Right now there is momentum, but in 2010 there was still a dark cloud hanging over it. People said: ‘This is complicated, we’re not sure it’s going to work; even if it does work, can you scale it, will people pay for it.’ We have a very simple philosophy – if you believe that you can have a dramatic impact on patients, then you can solve a lot of other challenges.”

The development of its sickle cell therapy and beta thalassemia has been the epitome of the biotech rollercoaster, with very promising results in one sickle cell patient raising hopes, then failing to produce in other patients. In 2015 an advisory panel recommended the delay of trials in children with beta thalassemia for 1-2 years until more safety data could be obtained.

After these painstaking years of setbacks, step-by-step progress, and a few major breakthroughs, Leschly is confident his company can pull off this unprecedented feat of launching four first-in-class gene or cell therapies by 2022.

The company launched its IPO on the Nasdaq in 2013, and those years of ups and downs mean it is well known to investors – if not yet a household name. The firm currently has a market capitalisation value of $8.9bn, even before its first product launch.

This valuation puts it far ahead of competitor Spark Therapeutics (currently worth $3.31bn), even though its rival has Luxturna, a rare blindness treatment and the first-ever FDA approved gene therapy, already on the market.

Gilead and Novartis aside, the only companies with a stake in gene therapy with a higher market capitalisation are BioMarin, in pole position to develop a potentially curative therapy for haemophilia A gene therapy, and Duchenne pioneer Sarepta.

The analyst perspective

Raju Prasad is a gene therapy specialist analyst at William Blair and says Bluebird’s management team has done a very solid job in taking the company this far.

He commented in an investment note: “While the current valuation [of Bluebird] does reflect steep expectations, we view each of their late-stage clinical products as having the most mature data set in their respective indications, and believe they are best in class.”

Talking to PME about the now burgeoning gene therapy field, Prasad says Bluebird and Spark Therapeutics deserve credit for investing in the field ten years ago when many others doubted its value.

On to 2018 and investment is flooding into the field: in June no fewer than three new gene therapy companies (Avro, Magenta, and Unum) launched initial public offerings.

“It’s important to recognise that Spark and Bluebird have been real pioneers in the space,” says Prasad, who credits them and a few academic partners for maintaining research when others didn’t believe in its potential. “If you look at how many gene therapy companies there are – if you include Gilead and Celgene there are easily 25-30, and investment in the cell and gene therapy space is at an all-time high and valuations are growing.

“It’s going to be very interesting to see where it goes, and how ingrained these therapies will be in our normal healthcare delivery. That remains to be seen, but that’s the next challenge.”

A step change in manufacturing

Key to Bluebird’s success so far has been investing over the long term in its gene therapy platform and striving to constantly improve it.

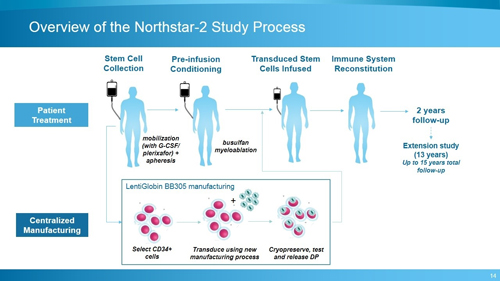

In particular, it set out to refine its manufacturing process to increase the percentage of cells successfully transduced (the transfer of the gene into a cell by the viral vector), which can be measured by increasing vector copy number (VCN) in the drug product.

The new refined process, used in its Northstar 2 trial has been shown to produce three times as many cells; the proportion of CD34+ transduced cells was 82%, compared with 32% in the original process.

Prasad says Bluebird’s continued focus on improving its product is building confidence in it and the broader gene therapy field.

“That’s a huge boon for the entire gene therapy space, because it means other companies don’t have to explain ideas such as ‘engraftment’ or what ‘vector copy number’ is. These aren’t run-of-the-mill ideas; the science is pretty complicated. So achieving that process of improvement, communicating that to investors and then showing pretty clear clinical benefits or biomarker benefits is extremely important, not just for the company, but for the field as a whole.”

Leschly says his company has achieved two or three systematic advancements in its platform, which are now paying dividends across its pipeline.

“At EHA people already had expectations in thalassemia – the data was already impressive – but they didn’t know quite what to think about our potential sickle cell therapy. I think this data puts us in a space that injects an infusion of optimism.”

I asked Leschly if the latest data made him more confident about describing Bluebird’s gene therapy as a cure for these conditions.

“The one thing we take very seriously for patients and families is that if we over-promise and under-deliver, no-one would want that. I know everyone likes to dream; we’re dreamers like anyone else, so we try to be a little bit more cautious on that front.

“That said, for thalassemia, and for sickle cell, we believe these are potentially one-time curative treatments, because these stem cell transplants have been shown to last a very long time, if not a lifetime. We don’t see why, if it is producing enough haemoglobin once it stabilises, it can’t be in the curative realm.”

Why Europe first?

Bluebird’s decision to file its LentiGlobin TDT with the European Medicines Agency first, rather than the FDA, is highly unusual, and is based very much on the European regulator giving the therapy its PRIME designation in September 2016.

PRIME (The PRIority Medicines scheme) provides enhanced interaction and early dialogue with developers of promising medicines, but isn’t a direct copy of the FDA’s Breakthrough pathway, even though both systems do select primarily on novel treatments for areas of high unmet need. In particular, it has looked to help small- to medium-sized companies and, eye-catchingly, also involves early dialogue with Europe’s payers and health technology assessment bodies.

“We give huge credit to EMA regulators,” says Leschly. “I’d go as far as to say that if it wasn’t for some of those [European] authorities, that Bluebird might not even be in existence, because they have been very supportive and patient in enabling us to run clinical studies.

“When we showed them the data on thalassemia they said, wow, that is impressive, let’s push forward. The US has been a little bit more conservative, still actually quite reasonable, and now even more reasonable now that the agency is under Dr Gottlieb.”

He says Bluebird found the EMA more engaged, and clinical sites were willing to move a little faster.

“We didn’t sit down and say 'we want to launch in Europe first', it was more a question of 'where will someone let us play?'”

Nevertheless, it seems reasonable to predict that, as gene therapy becomes better established, the FDA and EMA approaches are likely to converge over time, although for now the two agencies are developing their own advance therapy frameworks.

Learning from the failures of Glybera and Strimvelis

When Spark Therapeutic’s Luxturna gained FDA approval last year, it was the first US-approved gene therapy, but Europe was years ahead in approving the first two gene therapies anywhere in the world.

The EMA approved the world’s first ever commercialised gene therapy, UniQure’s Glybera, in 2012, a treatment for lipoprotein lipase deficiency (LPLD), a rare inherited disorder which can cause severe pancreatitis. Then GSK’s Strimvelis followed in 2016 for a very rare disease called ADA-SCID (Severe Combined Immunodeficiency due to Adenosine Deaminase deficiency).

However, while groundbreaking, both treatments have proven to be costly commercial failures: UniQure withdrew Glybera from the market last year, having treated just a handful of patients – held back by its huge price tag of 1.1m euros ($1m), which made it officially the world’s most expensive drug.

It was also held back by huge bureaucracy around its pricing and reimbursement, and a lack of buy-in from payers in Europe. Objections to the price tag were made worse because health systems had to pay upfront for the medicine, even though there was no guarantee the patient would respond.

GSK has also had very limited success with Strimvelis and has now sold on the treatment to UK-based gene therapy specialists Orchard Therapeutics.

Even though they didn’t end up being commercial successes, these approvals have put the EMA in the vanguard of gene therapy – and demonstrated to companies such as Spark and Bluebird which pitfalls to avoid.

Cell and gene therapy – disrupting pharma’s tried-and-tested model?

There is no doubt that the promise of a ‘one and done’ gene therapy poses certain problems – not just for payers, but for the industry as well.

In April this year, a Goldman Sachs biotech report suggested that curing patients, as many gene therapies promise to, is not a good business model.

This observation was seen as controversial – of course the goal should always be a cure. At the same time it confronted the fact that pharma has prospered on making drugs which require long-term treatment, eg HIV antiretrovirals, as they produce a long-term revenue stream.

Cell and gene therapies undoubtedly do pose difficult questions – but there is also no question of holding back because of this business model uncertainty.

Prasad thinks Bluebird’s commercial model is viable, just as long as it listens to the mood music from payers.

Engaging with governments in Europe upfront is going to be very important, as they do the majority of buying from a drug perspective, and Bluebird’s head of European operations Andrew Obershain is now well advanced with these discussions.

“The important thing is that management doesn’t ignore the realities of health spending in respective countries,” says Prasad. “I think a seven-figure price tag in this type of political climate would be a bit tone deaf.”

That means gene products hitting that Glybera price of $1m are, for now at least, unlikely.

Prasad and his colleagues at William Blair assume the product will gain conditional approval in the EU in 2019 for non-ß0/ß0 patients and forecast a price of $550,000 for therapy as a blended average of the US and EU. A more modest price of $200,000 is predicted for the rest of the world for the therapy.

Bluebird are also likely to get the chance to benchmark their price against Spark’s Luxturna which is on course to gain EU approval by the end of 2019.

Spark has signed a marketing deal with Novartis in Europe, which means the big pharma company will set the price – with its own CAR-T treatment Kymriah and Gilead/Kite’s rival Yescarta also providing price guides once they gain approval, also likely by the end of this year.

"It’s not difficult to envisage a value-based payment model where the patient comes for a test every year to see if their haemoglobin is still significantly elevated and that they’re still transfusion-independent, and then you simply mark off another year of payment."

US prices for Novartis’ Kymriah and Gilead’s Yescarta are $475,000 and $373,000, respectively, for the one-off treatments.

Bluebird is strongly advocating an annuity-type approach – where instead of having to pay the whole cost upfront, payers can pay off the bill in yearly instalments.

It also wants to use ‘value-based’ payment for its products, where healthcare systems only pay when the therapy works.

Raju Prasad says Bluebird can offer a compelling cost-effectiveness case for its treatment in beta thalassemia and sickle cell cases versus conventional stem cell treatment. Conventional stem cell transplants cost anywhere between $500,000 and $1m, while also carrying the risk of having to treat adverse events such as gvhd for example.

“It’s not difficult to envisage a value-based payment model where the patient comes for a test every year to see if their haemoglobin is still significantly elevated and that they’re still transfusion-independent, and then you simply mark off another year of payment.”

Bluebird’s strategy is to take the long view on pricing, and it says it wants to work in collaboration with insurers and healthcare systems to adapt payment systems, and is prepared to lay the groundwork for the whole field.

William Blair estimates that LentiGlobin worldwide revenues could exceed $800M in worldwide revenue in TDT, but this depends very much on whether subsequent data shows it can provide curative treatment in those harder-to-treat ß0/ß0 patients.

“What remains to be seen is the ß0/ß0 genotype population and whether they are able to produce more robust results compared to their initial Northstar data set,” says Raju. “We’ll get that information or at least an early signal at the ASH congress in December.”

Beyond the first filing

While Bluebird may have cleared many of the hurdles of safety and efficacy for its lead drugs, there is undoubtedly more turbulence to come. This is especially likely around its multiple myeloma candidate bb2121, where competition will be fierce from rival multiple myeloma CAR-Ts, such as J&J and Legend Biotech’s candidate LCAR-B38M.

There are other challengers in the field – Celgene and Acceleron look set to file their own beta thalassemia product, which looks set for filing after encouraging phase III data was released in July. However this small molecule drug promises more modest treatment benefits, and only in patients with milder cases of the disease.

CRISPR Therapeutics, one of the companies working with the exciting cutting-edge CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology, is looking to begin a phase I trial with Vertex on a candidate for sickle cell disease. However the FDA placed a clinical hold on the IND for the candidate in May, suggesting that field is where gene therapy was about five years ago.

Naturally there is near-continuous speculation about whether a big pharma company will swoop in to acquire Bluebird, especially following Gilead’s $11.9B buy-out of Kite, and Celgene’s $9B acquisition of Juno.

Leschly says he and the company’s growing flock of ‘Bluebirds’ (now 600 strong) have shown themselves to be disciplined at staying focused on the science and delivering for patients, even when expectations run high and send its stock soaring and crashing on a regular basis.

“That is one of the things we’re proudest about on a cultural level in Bluebird… that stuff really just bounces off us. We obviously had a lot of excitement around our first sickle cell patient, the stock shot up and then it shot down. I was proud because the way the team responded to that scientific challenge was unbelievable and largely, if not completely, ignored the ups and downs of what was going on outside.

“The fact that we have the potential to help change the face of medicine – that’s what we think about. All that volatility, quite honestly, is interesting, but it doesn’t change our true North.”

Source: Bluebird Bio